As Hungary heads toward April elections, the opposition Tisza party presents a pro-European governing platform

Hungary is approaching one of its most politically consequential elections since 2010. For more than a decade, the country has been governed by Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party, which have consolidated power through repeated parliamentary supermajorities.

This dominance has rested not only on electoral success but also on a deep restructuring of the institutional and media landscape. Public broadcasting, much of the private media market, and significant segments of the advertising economy operate within a pro-government ecosystem, shaping political communication and limiting pluralistic debate. While elections in Hungary remain formally competitive, they take place in a system that structurally favours incumbency, particularly through a mixed electoral system that amplifies constituency victories and rewards disciplined nationwide organisation.

The parliamentary election scheduled for April will therefore be held under asymmetric conditions. Fidesz enters the campaign with extensive control over state resources, a loyal media environment, and well-established local networks, particularly outside major urban centres. At the same time, economic stagnation, strained public services, and the prolonged freezing of EU funds linked to rule-of-law concerns have eroded the government’s credibility among segments of the electorate. It is within this context that the emergence of the Tisza Party represents a potentially disruptive development.

The new power contender in Hungary

Tisza is a relatively new political formation, but it has rapidly positioned itself as the most serious electoral challenge Orbán has faced in years.

The party is led by Péter Magyar, a former insider of the governing system who broke publicly with the Orbán establishment in 2024. His background differentiates him from previous opposition leaders: rather than coming from the traditional liberal or left-wing opposition, Magyar presents himself as a conservative reformer who understands the internal mechanics of power and corruption in Hungary. This profile has allowed Tisza to appeal not only to opposition voters but also to disillusioned Fidesz supporters, a constituency that earlier challengers largely failed to penetrate.

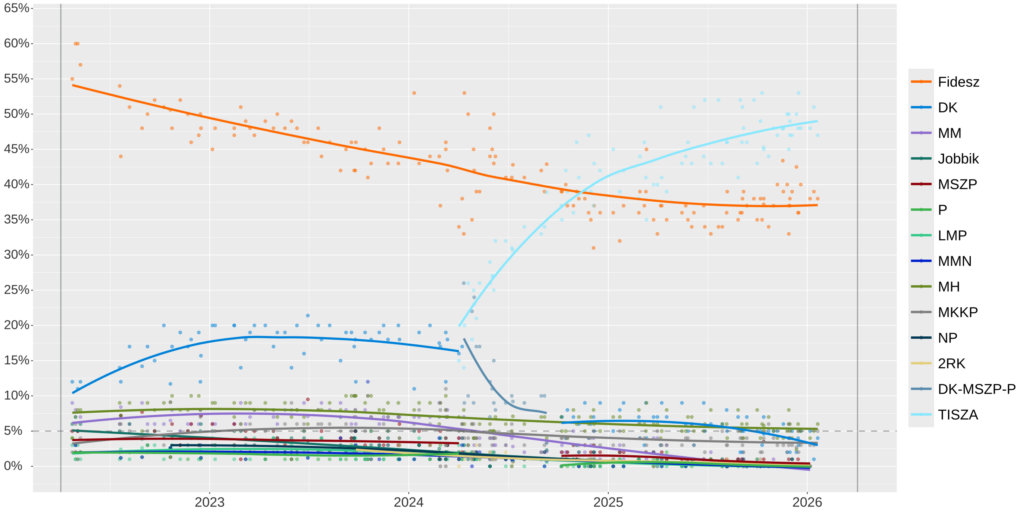

Polling data suggest that this strategy has yielded tangible results. Independent surveys show Tisza leading Fidesz among decided voters by high single-digit or even double-digit margins, although pro-government pollsters continue to report a Fidesz advantage and a substantial share of the electorate remains undecided. As in previous Hungarian elections, headline vote shares are only part of the picture: the decisive factor will be whether Tisza can translate national momentum into victories in single-member districts, where organisational capacity, candidate visibility, and local campaigning are critical.

A programme built around European re-anchoring

The publication of Tisza’s 240-page election programme marks a further step in its attempt to consolidate credibility as a governing alternative. Titled “The foundations of a functioning and humane Hungary,” the programme is notable less for radical innovation than for its deliberate repositioning of Hungary within a mainstream European political and economic framework. It combines social and fiscal measures with a clear geopolitical reorientation, explicitly reaffirming Hungary’s anchoring in the European Union and NATO.

On the economic front, the programme proposes a progressive rebalancing of the tax system, including income tax reductions for earners below the median wage and the introduction of an annual wealth tax on assets above one billion forints. These measures are framed not as punitive redistribution but as instruments to restore social cohesion and fiscal sustainability. More politically significant, however, is the programme’s emphasis on governance and corruption. Tisza presents the unfreezing of EU funds as a central economic priority, arguing that credible rule-of-law reforms would unlock billions of euros needed to stabilise growth and modernise public services.

The programme also outlines an ambitious agenda for reforming healthcare, education, welfare, child protection, and public transport – sectors widely perceived as deteriorating under prolonged underinvestment. While many of these pledges would require multi-year implementation and significant administrative capacity, their inclusion reflects an attempt to shift the political debate away from identity and sovereignty narratives toward state performance and service delivery.

From a European and security perspective, the most consequential elements concern energy and strategic orientation. Tisza commits to ending Hungary’s dependence on Russian energy by 2035 and to significantly increasing the share of renewables by 2040. While maintaining support for nuclear power, it pledges a comprehensive review of the Russian-built Paks II nuclear project, signalling a willingness to reassess long-term strategic dependencies. The programme also commits to setting a realistic target date for euro adoption, a move that would symbolically and economically deepen Hungary’s integration into the EU core, though actual entry would depend on demanding fiscal and institutional convergence criteria.

Electoral constraints and scenarios

Despite this programme and favourable polling, the electoral outlook remains highly uncertain. Tisza faces formidable structural obstacles: a media environment largely hostile to opposition messaging, an electoral system that rewards incumbency, and the difficulty of mobilising undecided voters in rural constituencies. Moreover, Orbán continues to benefit from coordinated political support beyond Hungary’s borders, including public endorsements from figures associated with the global populist right, reinforcing his narrative of international legitimacy and ideological alignment.

A Tisza victory would therefore require not only sustained national momentum but also an exceptional performance in constituency races and voter turnout. Failure to secure a clear parliamentary majority could result in a fragmented legislature, complicating governance even in the event that Fidesz loses its dominant position.

For Europe, however, even the credible prospect of a Tisza government already carries implications. A change in leadership in Budapest would likely ease persistent tensions within the EU over rule-of-law enforcement, sanctions policy, and common foreign positions. While a Tisza government would not automatically resolve institutional disputes or guarantee rapid euro adoption, it would signal a strategic re-alignment of Hungary toward cooperation rather than confrontation within the Union. In a period marked by geopolitical instability and internal EU fragmentation, that shift alone would represent a meaningful change in Europe’s political balance.

In that sense, the Hungarian election is not only a national contest but a test of whether political alternation remains possible in systems shaped by long-term incumbency – and whether the European centre of gravity in Central Europe can still move.

Leave a Reply