As the saying goes, history always repeats itself: first as a tragedy, and later as a farce.

The European political debate today is saturated with discussions about free speech – a debate that increasingly appears to pit European governments against the United States’ government and its most prominent supporting tech oligarch, Elon Musk.

The script is remarkably consistent across European countries. A European politician attempts to put a brake on online manipulation, disinformation campaigns, or misconduct by social media platforms, only to be overwhelmed by coordinated attacks accusing them of censorship and suppression of free speech.

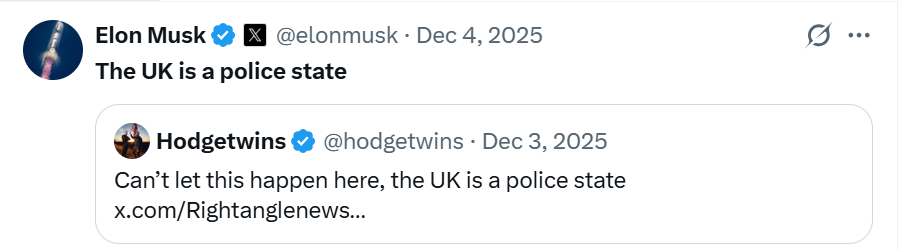

The attack typically begins on X, where Elon Musk beats the drums before his community of 231 million followers, amplifying a questionable reinterpretation of events through a post originating from a “Musk-friendly” ecosystem account.

Outrage then grows and boils. Hundreds of faceless accounts flood comment sections under every related news item, relentlessly promoting a Musk-aligned version of reality. The story spreads, and a new political enemy is manufactured.

The second phase is the official reaction. A U.S. government official announces that the country in question may face sanctions, or retaliation should it attempt to limit “free speech” or impose regulations on U.S. technology platforms.

Soon after, the internal front opens. Groups of political leaders – often aligned with or sympathetic to the MAGA political sphere – reinforce the narrative promoted by Washington: Country XYZ is censoring free speech and cracking down on freedom.

These same political actors – whether the Reform UK party of Nigel Farage, Italy’s Lega under Matteo Salvini, France’s Rassemblement National led by Marine Le Pen, or Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland – tend to be far more cautious when it comes to condemning the blatant repression of political rights and freedoms elsewhere, for example in Russia, toward which they all maintain conspicuously lukewarm positions.

The latest episode of this farce is unfolding before our eyes. The UK government under Keir Starmer, considering the introduction of limits on X, has been attacked and accused of censorship both domestically – from the aforementioned Reform UK – and from across the Atlantic, through official reactions and threats issued by the U.S. government.

The Quing dynasty and the Opium war

Yet before becoming the farce we witness today – populated by figures as clownish as Elon Musk himself and the would-be Nobel Peace Prize laureate Donald Trump – this story had already played out in far more tragic terms in the mid-nineteenth century, in the Chinese Empire, where the British Empire flooded local markets with opium grown in India to offset its trade deficit.

At the time, China was governed by the Qing dynasty, an autocratic imperial system cantered on the emperor and a vast bureaucratic elite selected through civil service examinations. In theory, this system emphasized stability, hierarchy, and moral governance; in practice, it struggled to adapt to a rapidly changing global order.

Power was highly centralized, slow-moving, and resistant to foreign influence or technological innovation. While the empire remained territorially vast and culturally confident, it underestimated European military and economic power. Internal challenges – population growth, fiscal strain, and bureaucratic corruption – further weakened the state, leaving it ill-prepared to confront the pressures by colonial powers.

The export of opium to China, which expanded rapidly from the late 18th century and intensified after 1800, had a profound and destabilizing impact on Chinese society. What began as a commercial solution to Britain’s trade deficit soon evolved into a social crisis: millions became addicted, labour productivity declined, and silver flowed out of the country, weakening China’s economy.

Beyond its social consequences, opium undermined state authority. Widespread corruption emerged as officials accepted bribes to ignore bans, while the Qing government’s repeated but ineffective prohibitions exposed its inability to enforce policy.

The opium trade thus became not only a public health disaster, but a political one, eroding confidence in imperial rule and revealing China’s vulnerability to foreign economic pressure.

The first Opium war erupted when the Qing emperor moved decisively to enforce the long-standing ban on opium imports and suppress the trade in the southern port of Canton in 1839. The emperor ordered foreign merchants to surrender their opium stocks and ordered the destruction of more than 20,000 chests in a public demonstration of imperial authority.

Britain, however, interpreted this action not as a legitimate enforcement of Chinese law but as an attack on British property and commercial rights. Determined to preserve its economic interests and political influence in East Asia, the British government responded with military force, deploying its modern navy to compel China to reopen its markets.

What began as a dispute over contraband escalated into a full-scale war, exposing the clash between China’s sovereign authority and Britain’s imperial need to keep the massive Chinese opium market open for the interest of its merchants.

The First Opium War was resolved in 1842 with China’s defeat and the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, which marked a turning point in China’s relations with the Western powers. Under the treaty, China was forced to pay a substantial indemnity, open five treaty ports to British trade, and cede Hong Kong to Britain, while granting foreign merchants unprecedented privileges.

These concessions failed to bring stability. Continued tensions over trade, diplomacy, and legal jurisdiction led to the Second Opium War (1856-1860), during which Britain, joined by France, pressed for further access and rights. China’s renewed defeat resulted in even harsher settlements, including the legalization of the opium trade, the opening of additional ports, and the permanent presence of foreign legations in Beijing, deepening foreign influence and further undermining Qing sovereignty.

In Chinese history and political memory, these events are remembered as founding elements of what is called the “Century of Humiliation,” a period roughly spanning from the Opium Wars of the 1840s to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. This era is defined by repeated military defeats, the imposition of unequal treaties, territorial losses, and sustained foreign intrusion into China’s sovereignty.

In modern Chinese political discourse, the Century of Humiliation continues to serve as a powerful historical reference point, shaping nationalism, state legitimacy, and China’s enduring emphasis on sovereignty and resistance to external domination.

Stopping today’s opium merchants

Fast forward to 2026, Europe, a still economically rich and influential continent, is faced with an existential dilemma: should we allow the today’s oligarchs and opium merchants addict our societies to algorithms that risk destabilising, undermine, and manipulate our democracies in favour of foreign powers?

This same dilemma confronted the United States between 2024 and 2025, when the U.S. government moved to force TikTok, a Chinese-based and state-influenced social media platform, either to divest from its Chinese parent company or face a nationwide ban. The prescribed remedies included the mandatory separation of ownership from China-based entities, strict controls over U.S. user data storage, enhanced transparency over recommendation algorithms, and the possibility of independent security audits.

Washington explicitly framed the platform as a national security risk – not merely because of data access, but because of its capacity to shape opinion through addictive and behaviour-modifying algorithmic design.

Today, however, European states are confronted with a striking contradiction.

The same U.S. government that justified intervention against foreign digital influence now argues that Europe should not restrict the reach or power of American technology conglomerates within its own democratic space – despite simultaneously adopting confrontational positions toward European territorial integrity, as illustrated by renewed rhetoric concerning Greenland, and openly criticizing European regulatory and political models in recent U.S. strategic doctrine.

The parallel with the Opium Wars is difficult to ignore. Nineteenth-century China was told that resisting an addictive foreign commodity violated the principles of free trade; modern Europe is told that regulating manipulative digital platforms violates the principles of free speech.

In both cases, the central question is not commerce, but sovereignty: whether a society retains the right to defend its political independence against external forces that profit from dependence and manipulation.

The lesson of the Opium Wars is not merely historical – it is a warning about what happens when foreign economic power is allowed to override self-preservation: react in time or face a “century of humiliation“.

Foreign technological dominance is not inevitable. Unlike nineteenth-century China, today individual consumers retain meaningful agency: everyday digital choices can materially limit foreign influence, political meddling, and economic dependency in Europe. For most digital services, credible and competitive EU-based alternatives already exist. Platforms such as European Alternatives and EU Alternatives offer clear, accessible catalogues of European solutions.

Leave a Reply